Financial Regulation Update

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Securities and Exchange Commission has finalized a rule that may encourage more companies to go public, by lowering costs and increasing flexibility during the IPO process.

- Another recent SEC rule aims to avoid conflicts of interest when brokers make recommendations to investors, while safeguarding customers’ access to these services.

- The Federal Reserve and other agencies continue rulemaking required by a 2018 financial reform law, including to better match rules for banks to the risk they pose to the financial system.

This year, the Securities and Exchange Commission finalized a rule aimed at encouraging more companies to go public by allowing them to get information on market interest earlier in the process. It also finished a rule to prevent conflicts of interest when broker-dealers give investment advice to customers. As the Federal Reserve and other agencies implement a financial regulation reform law enacted in 2018, they have completed rules tailoring prudential standards to banks’ size, complexity, and risk.

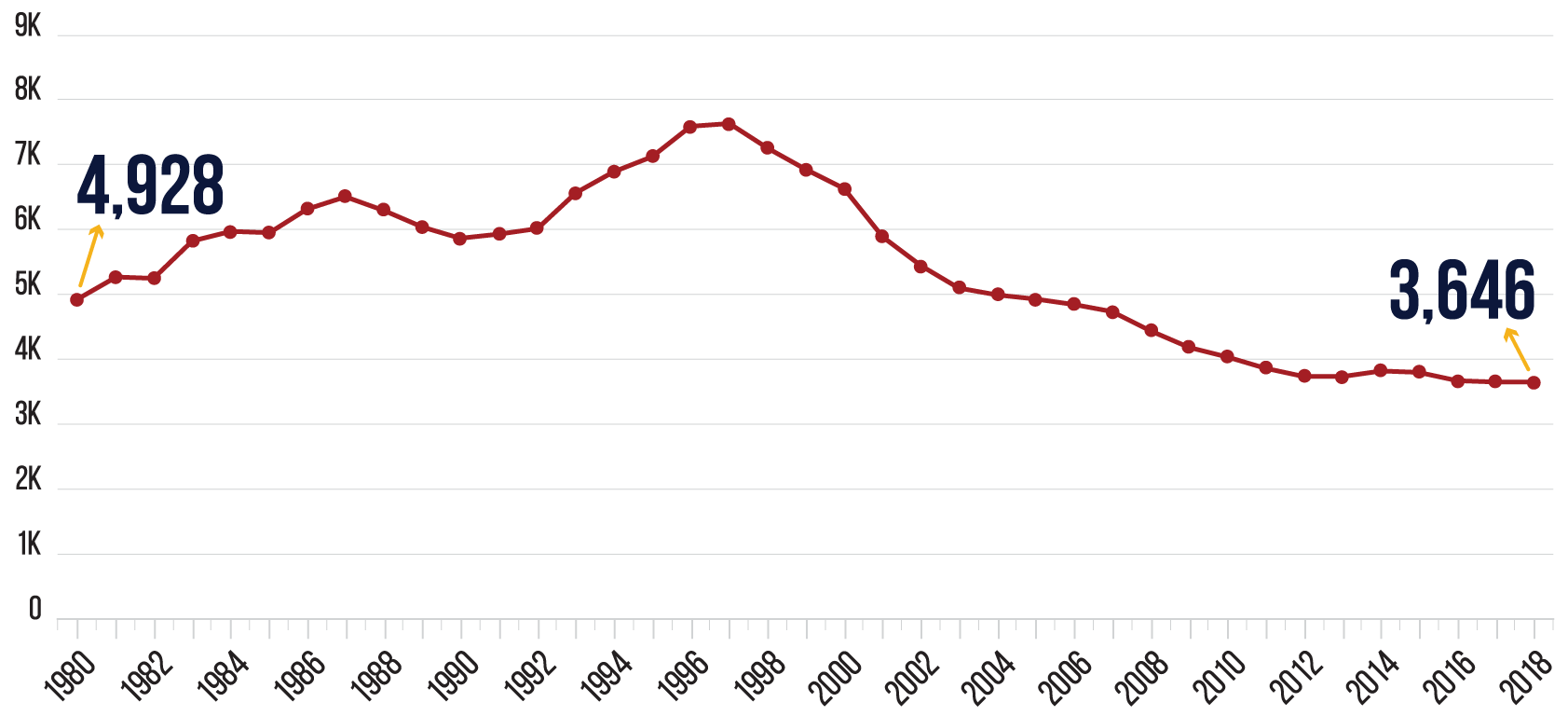

The Number of U.S. Publicly Traded Companies Has Declined

enhancing access to public markets

A new SEC rule, which will go into effect December 3, will help companies measure the market’s interest level before they decide to go public. It allows more companies to talk with investors about going public before filing registration documents with regulators. Companies that decide not to go public can avoid releasing proprietary information and save on filing costs. Some may avoid having to withdraw from a public offering, so the commission expects the rule to make public securities offerings more likely to succeed. A 2012 law made this accommodation for “emerging growth companies,” but larger ones were excluded until now.

The rule’s potential to reduce costs may encourage more companies to go public. This could benefit small investors, who would have an opportunity to buy the stock or own it through investment funds. The number of U.S.-listed firms was roughly 4,900 at the end of 1980. It rose through the 1990s but declined to about 3,600 by the end of 2018. The drop has been attributed to mergers, delistings, and fewer companies going public. University of Florida researchers found there were an average of 310 initial public offerings per year from 1980-2000, but only 108 per year from 2001-2016. There are different views on why there has been a decline and what having fewer publicly traded companies means for investors. SEC chairman Jay Clayton has said it is a problem: “to the extent companies are eschewing our public markets, the vast majority of Main Street investors will be unable to participate in their growth. The potential lasting effects of such an outcome to the economy and society are, in two words, not good.”

protecting small investors

The SEC also adopted a set of rules in June to clarify the standards for how financial advisers and broker-dealers interact with their clients. It comes after the courts halted a related rulemaking from the Obama administration’s Labor Department, saying it had exceeded its authority.

Under part of the rule package, broker-dealers must make recommendations in the best interest of their customers. This is designed to protect small investors, preserve customers’ access to investment services, and increase transparency. The new standard requires brokers to use “reasonable diligence, care, and skill” when working with customers and to consider the client’s particular situation. They must tell customers about all fees and the types of services they will provide. Brokerages must also set up business policies to mitigate or avoid conflicts of interest, such as sales contests and quotas. The rule took effect in September, but brokers have until June 30, 2020, to comply.

The SEC is coordinating with the Labor Department, which is working on a related rule to clarify the standards that financial advisers must meet when giving retirement investment advice.

tailoring bank oversight

Part of the financial regulatory reform law enacted in 2018 required the Federal Reserve Board of Governors to reexamine the post-financial crisis prudential standards for certain banks and to simplify the regulations. In October, the Fed, in collaboration with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, released rules that tailor the standards to the level of risk large banks pose to the financial system.

Banks covered under the rules are put in one of four categories based on their size and other risk factors. Category one has the global systemically important banks, while category four has smaller banks with $100 billion to $250 billion in assets. Systemically important banks still must adhere to the most stringent standards. Firms in the other categories receive some relief under the rules. These banks will be subject to progressively simpler rules for capital and liquidity requirements, as well as how often they must run stress tests predicting their performance in an economic downturn.

A related rule the Fed and FDIC finalized in October changes how frequently banks must submit plans outlining the steps they would take if they fail. Large banks that pose the most systemic risk would submit these plans, sometimes called “living wills,” every two years, while other banks generally posing less risk would be on a three-year cycle.

Next Article Previous Article