Asylum and the Refugee Law Update

KEY TAKEAWAYS

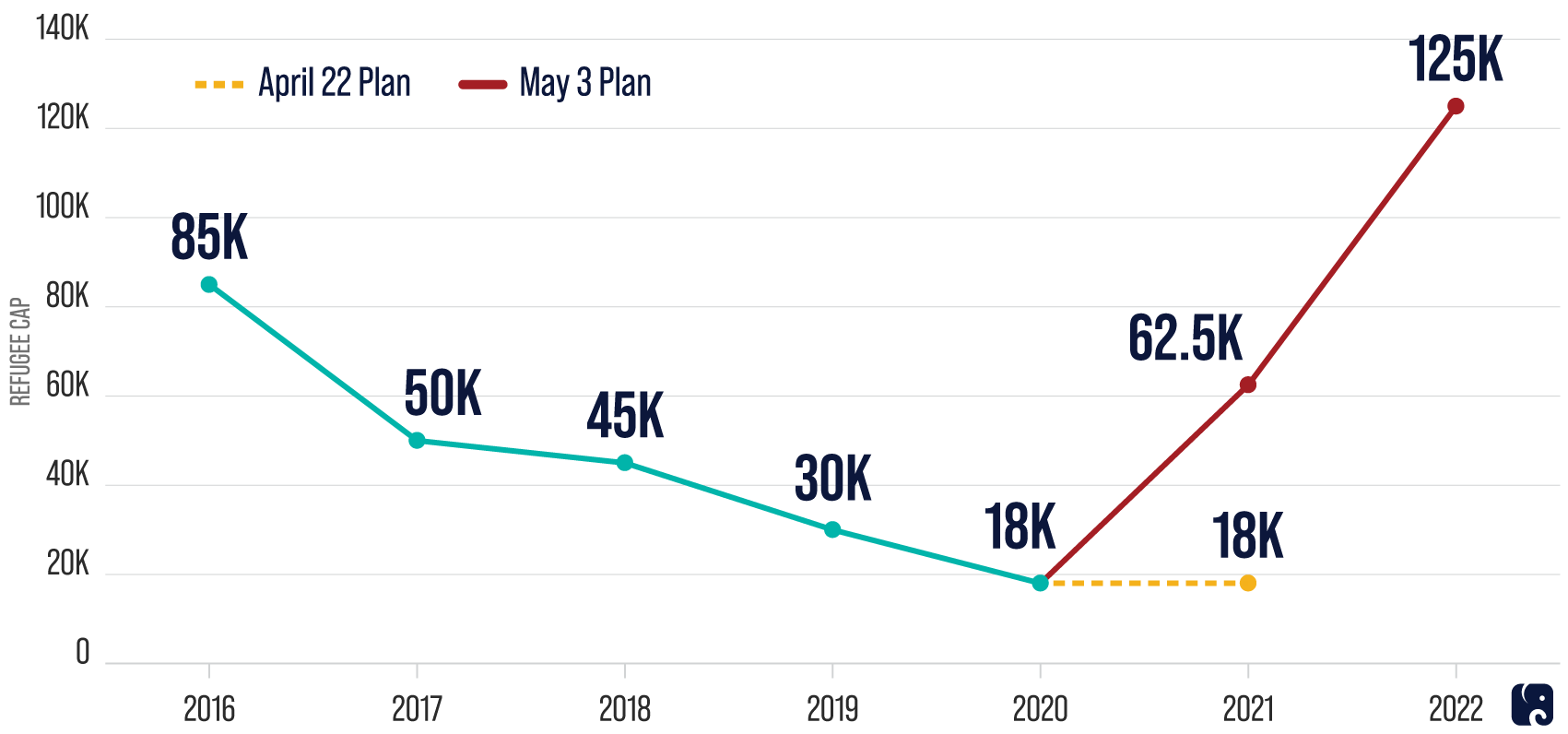

- Days after the White House announced it would keep the Trump administration’s 18,000-refugee cap, President Biden flip-flopped and raised the cap to 62,500.

- The Biden administration has rescinded or begun the process of repealing several changes President Trump made to asylum law.

- The administration has yet to present a detailed plan to address the vast backlog of asylum claims or the ongoing surge in new claims.

The Biden administration has struggled to offer a clear vision for immigration law. Facing criticism of its handling of the border crisis, the White House announced on April 22 that it would maintain the Trump administration’s 18,000-refugee cap, the lowest since at least 1980. Less than two hours later, when the announcement generated negative press coverage, the White House said President Biden would increase the cap later. President Biden then announced on May 3 that he was increasing the fiscal year 2021 cap to 62,500 and declared a goal of 125,000 refugee admissions for 2022.

The Biden Administration Refugee Cap Flip-Flop

The cap decision was driven by political fears, not a coherent plan. The administration’s flip-flop on the cap did nothing to change the facts. As of May 10, the U.S. had admitted 2,334 refugees in fiscal year 2021, and it is unlikely to reach even the 18,000-refugee cap because the administration did not make adequate preparations to increase admissions. The cap itself has no direct effect on the border crisis because all refugees apply from overseas, while people already at the border file asylum claims.

The Biden administration’s vacillation on refugees mirrors its lack of vision in asylum law. The administration rescinded the Remain in Mexico program and suspended asylum cooperative agreements with the three Northern Triangle countries – Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador – that allowed the U.S. to send asylum seekers to have their claims adjudicated there rather than in the United States. At the same time, President Biden left in place the Trump administration’s public health emergency, allowing it to reject the entry – and, hence, the asylum claims – of most migrants who show up at the southern border.

The current uncertainty reflects a decision not to decide between two logical plans: admit more asylum seekers and refugees, or restrict admissions to deter all but the most desperate. What will certainly not work is making vague pro-admission noises, but not taking any steps to make the system work more smoothly.

THe Problem of Asylum Law

Regardless of political preferences for more or fewer asylum admissions, there are far more people who want to claim asylum than there is capacity to process the claims. The scope of the problem is daunting.

In fiscal year 2019, the most recent for which complete data is available, the U.S. granted asylum to 7,622 people from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras combined. During the pandemic, the United States has summarily expelled more than 600,000 migrants at the border on public health grounds. There is a backlog of 613,000 asylum applications making their way through the system, with the average case now taking about 2.5 years to complete.

As bad as those numbers are, the problem will likely get worse. The United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic would push 45 million people throughout Latin America into poverty. Economic strife tends to increase asylum applications by destabilizing countries of origin and creating a larger incentive to come to a developed country with a stronger economy.

Strategies for Fixing the Asylum System

Without statutory changes by Congress, any presidential administration faces limits on what it can do to fix the system for deciding asylum claims. There is general support among the American people for at least some asylum admissions for those with valid claims. International law also requires the U.S. to have some kind of asylum system, so presidents cannot simply refuse to allow all claims. What presidents can do is calibrate the legal process to deter frivolous asylum claims and work to make the system operate in a more efficient manner.

The Trump administration intended to deter asylum claims in the first place by making the process more difficult for the asylum seeker. At the same time, it tried to make the process faster to reduce the overall burden on the system. The administration announced rules making it easier to dismiss cases through streamlined adjudication, though those rules were stayed in court and never went into effect.

In another initiative, migrants could make asylum claims, but they might be forced to remain in Mexico while the claims were adjudicated, which could take years. Under the terms of cooperative agreements with the Northern Triangle countries, the U.S. could send asylum seekers to have their asylum claims adjudicated in that region rather than in the United States. In 2019, the Trump administration proposed a Safe Third Country Rule that, with limited exceptions, would have made migrants ineligible for asylum in the U.S. if they had failed to apply for asylum in a third country, such as Mexico, through which they had passed on their way to the southern border. The Trump administration also announced a zero-tolerance policy for illegal border crossing, which resulted in authorities separating some families of asylum seekers when the adults faced trial for crossing the border illegally.

The Biden administration has not announced a clear plan for fixing the asylum process. It has rescinded or begun the process of rescinding many Trump-era rules relating to the process, but it has not made any substantial efforts to make the system work more efficiently. The administration has also suspended the asylum cooperative agreements and is considering repeal of the Safe Third Country Rule. These actions have weakened the deterrence of asylum claims. The administration has kept in place the public health restrictions preventing the entry of some migrants, including potential asylum seekers, but it has also created exceptions to the public health entry restrictions for unaccompanied alien children and some other migrants deemed eligible for “humanitarian exceptions” to the restrictions.

Actual efforts by the administration to fix the asylum law problem have been sparse. The administration has pledged $4 billion in aid over four years to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador on the theory that fewer people will make the journey north to the United States if their home countries are improved. It is unlikely that aid will reduce asylum claims in the short run, and it may even increase them because people with disposable income are more likely to be able to afford the journey to America.

The refugee cap flip-flop and the tiny number of actual refugee admissions represent a missed opportunity. Admitting more refugees while deterring asylum claims could relieve pressure on the asylum system. In the short run, more refugee admissions strain the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement, which also cares for unaccompanied children on the southern border. The Biden administration has already transferred or reprogrammed almost $3 billion from COVID-19 supplemental appropriations, the American Rescue Plan, and other HHS programs to deal with the influx of unaccompanied children crossing the border. The FY 2022 budget request for ORR calls for more than doubling the funding for refugees and unaccompanied alien children, for a total of $4.4 billion.

In the long run, processing a greater share of migrants through the refugee system has several advantages. The migrants do not go through the immigration court system, reducing the backlog. Most refugees are referred to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program by international organizations, making vetting easier. The United States can and does vet refugees further before they arrive. All of this happens while the migrant is still outside the country, meaning fewer desperate people would make the dangerous journey to the southern border to enter the overwhelmed asylum process. Republicans on the Senate Appropriations Committee have noted that processing applications outside the United States allows for a smoother and more orderly process.

Next Article Previous Article