Taking on Genuine Tax Reform

The Senate Finance Committee has started with a “blank slate” approach to tax reform, in which all tax expenditures are eliminated. Advocates can add tax provisions back in if the provision grows the economy, increases tax fairness, or achieves “other important policy objectives.” The Chairman and Ranking Member note that Congress has made more than 15,000 changes to the tax code since the last tax reform in 1986. It is no wonder that it costs Americans 6.1 billion hours every year just to comply with the current tax code and figure out what they owe. Estimates for compliance costs range between $168 billion and $431 billion a year. This complexity is a boon for special interests, but that money could be put to far more pro-growth uses in our economy.

If revenue-neutral tax reform is successful, it could deliver a powerful “simplicity dividend” to the U.S. economy by getting the tax code out of the way of economic growth. The requirement that reform be revenue neutral is key. Democrats already got $660 billion in extra tax revenue in the December 2012 “fiscal cliff” deal. Additional revenue generated from tax reform would take even more money out of the private economy and put it in the hands of the federal government, which has proven it cannot spend its way to prosperity.

Tax Expenditures Have Grown Out of Control

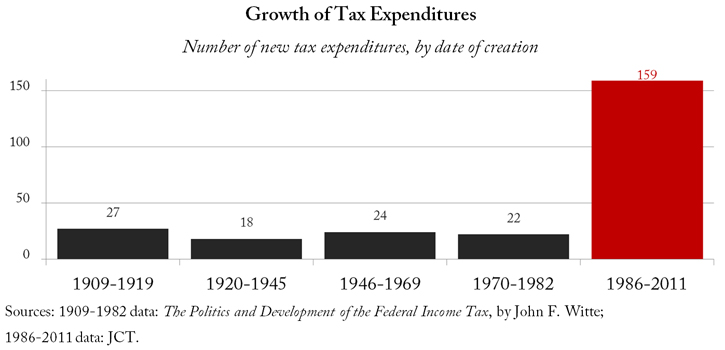

Tax expenditures have been with Americans since the first income tax to fund the Civil War. In that law, interest on government bonds was taxed at a lower rate, and a deduction was included for rent expenses, among other provisions. Although these special exemptions are not new, their use has increased greatly. In the first decade under the 1913 income tax, Congress created 27 tax expenditures. Although the Tax Reform Act of 1986 eliminated or scaled back many tax expenditures, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) reported in 2011 that 159 tax expenditures had been added back into the tax code over the following 25 years (18 of these have expired). Scrubbing the tax code again, and eliminating as many unjustified tax expenditures as possible, would allow Congress to get tax rates as low as possible.

Tax Expenditures Enlarge Government Power

Tax expenditures enlarge the power of government to influence its citizens’ private decisions. They take what had been private issues and make them subject to public debate – a legislature debating a tax break is often deliberating the moral worth or economic benefit of a private citizen’s behavior. This is sometimes justified by the view that “lawgivers make the citizens good by training them in habits of right action.” This approach inevitably enlarges government.

“[G]overnment should collect the minimum revenues needed to support and protect a free society and do so in a way that is, as far as possible, neutral in its effect on individual behavior. In its purest form, this means no individual deductions, credits or tax expenditures.”

– Phil Gramm, July 10, 2013

To see how dangerous this approach can be, look at the government’s mechanism for giving tax preferences from a different angle. What if the government taxed its citizens under a basic rate structure, but rather than giving tax breaks to those who participate in favored activities, it actually punished the taxpayers who did not participate in these activities by charging them a surtax? This seems far less benevolent. In fact, this is the exact structure found in Obamacare’s individual mandate tax. The mandate is a huge increase in government power, and it has the same result as tax expenditures – citizens paying unequal taxes based solely on their personal decisions.

Broaden the Base

By broadening the base and lowering rates, the tax code will get closer to the idea of “horizontal equity.” This is the idea that taxpayers of equal income should pay equal tax, regardless of how progressive the tax code is.

Tax expenditures violate horizontal equity by allowing one taxpayer to take a deduction or tax credit that another taxpayer with equal income cannot take, and thus pay less in taxes. Special tax preferences increase public perception that the tax system is unfair. Eliminating tax expenditures in a revenue-neutral way could conceivably increase public satisfaction with the tax code.

Special Tax Provisions Are Inefficient

Tax expenditures not only harm equality between equal-income taxpayers but also are economically inefficient in many ways.

- Government spending always includes some amount of waste and duplication.

- If taxpayers are incentivized to spend money on some specific thing because of a tax benefit, that reduces what they spend on other things.

- Encouraging certain behavior through the tax code can lead to perverse incentives. Credit card interest used to be deductible before the 1986 reforms, encouraging people to rack up credit card debt. The deduction for state and municipal bond interest encourages more borrowing by state and local governments, when they are already in a dire fiscal situation. The deduction for state and local income and sales taxes makes it politically more feasible for these governments to raise taxes rather than cut spending to close budget shortfalls.

- Tax expenditures have increased compliance costs and created an industry to help taxpayers wade through the expensive, complex morass that is our tax code. A simpler code could save Americans billions of dollars just on tax preparation each year.

Some Tax Expenditures May Be Good Ideas

Criticisms against tax expenditures that encourage citizens to behave in a certain way should not be read as a criticism of all tax expenditures. Some tax provisions may be necessary to identify the right tax base to ensure true neutrality in the tax code. For example, a lower tax (or no tax) on capital gains and dividends could ensure that income earned by a taxpayer is only taxed once. Allowing taxpayers to defer tax on retirement savings through 401(k) or IRA plans also can more accurately measure their income, since they are deferring that income until retirement.

Testifying before the Budget Committee in 2011, Scott Hodge of the Tax Foundation summarized the issue this way: “Over the past two decades, lawmakers have increasingly asked the tax code to direct all manner of social and economic objectives, such as encouraging people to: buy hybrid vehicles, turn corn into gasoline, save more for retirement, purchase health insurance, buy a home, replace the home’s windows, adopt children, put them in daycare, take care of Grandma, buy bonds, spend more on research, purchase school supplies, go to college, invest in historic buildings, and the list goes on.” All of these may be good things, but their favored tax treatment comes at the expense of other things that may be just as desirable. Without the incentives of tax expenditures, taxpayers would have spent, invested, or saved their money in some other way, benefiting some other part of the economy. The debate over which tax expenditures make sense and which create the wrong incentives is worth having.

Revenue-neutral tax reform, starting from a blank slate, can be a great opportunity for Congress to ensure that tax expenditures are economically efficient. At the same time, the tax reform should strive to broaden the tax base, lower rates overall, and not expand the size of government.

Next Article Previous Article