Sorting Out Puerto Rico's Fiscal Crisis

- Last week the House passed PROMESA, a bill that imposes on Puerto Rico a financial oversight board and gives the territory the opportunity to restructure its debt.

- The bill’s bankruptcy provisions are structured to protect creditors’ rights while ensuring that creditors, not taxpayers, bear the cost of bad investments.

- The bill entrusts the financial oversight board with resolving most of Puerto Rico’s difficult issues, including bankruptcy. Some question whether this trust is warranted or wise.

- Puerto Rico has demonstrated that it is unable to balance its budget and is willing to default in order to avoid real reform.

Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis continues to worsen, and on July 1 the territory has a $1.9 billion debt payment that it will not be able to make. To address this deteriorating financial situation, on June 9, the House passed the revised Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, H.R. 5278, with a majority of Republicans supporting (297-127; R: 139-103; D: 158-24). The bill establishes a Republican-majority financial oversight board to take control of the territory’s finances and push economic reform. The bill also stays creditor litigation temporarily to allow the island to get a handle on its finances, and it authorizes Puerto Rico to restructure its debt in a court-supervised bankruptcy.

A Financial Oversight board is necessary

Puerto Rico has demonstrated that it is unable to balance its budget and is willing to not pay its debts in order to avoid reform. Its public sector remains bloated, with the government the largest employer on the island. Tax collection is meager, and audited financial statements are long past due.

In an effort to avoid its debts, the island’s government attempted to pass its own bankruptcy law, which the Supreme Court rejected this week. In April, it passed a debt moratorium law authorizing the governor to stop all debt payments in order to prioritize government expenses. This law is still in effect. Earlier this month a government-sponsored public debt audit commission even suggested that part of the island’s debt is unconstitutional and unenforceable.

“Since Puerto Rico approved a debt moratorium this spring, the choice is between a chaotic default dictated by the island’s spendthrift politicians and an orderly debt restructuring guided by Congress.” – Wall Street Journal, 06-13-2016

PROMESA imposes a financial oversight board to correct Puerto Rico’s mismanagement, return it to financial stability, and reestablish credibility with creditors. The oversight board would have seven members appointed by the president, with four chosen from a list provided by the Senate majority leader and House Speaker. Members would serve three-year terms. The board would have the power to impose a fiscal plan and budget on the territory; block legislation and government actions that don’t comply with the fiscal plan; cut expenses to balance the budget; and control Puerto Rico’s restructuring decisions.

Democrats criticize the board for overriding Puerto Rico’s sovereignty. This ignores the simple fact that Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory. The Constitution authorizes Congress to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory ... belonging to the United States.”

Some Republicans are concerned that PROMESA puts too much trust in the board to resolve competing interests. While the board is required to respect creditor priorities, it is also required to “provide adequate funding for public pension systems” and to seek a sustainable level of debt. With a Republican majority, the board is more likely to resolve these conflicts fairly, but if it does not, Republicans will be held accountable for the outcome.

Some also argue that the board has too little power to make changes that encourage economic growth. While pro-growth reforms are necessary to Puerto Rico’s long-term stability, economic growth is impossible with continued fiscal uncertainty. Puerto Rico needs a way to balance its budget and manage its debt obligations now.

Bankruptcy is not a bailout

PROMESA’s bankruptcy provisions also are controversial on the right. Some have argued that bankruptcy is a bailout for Puerto Rico. This argument inverts the traditional understanding of “bailout.” Taxpayer bailouts, such as the Troubled Asset Relief Program in 2008, give taxpayer money to collapsing institutions in order to prevent creditors and shareholders from losing money. They transfer the losses from creditors to taxpayers. Giving Puerto Rico bankruptcy access would do the opposite. It ensures that creditors, not taxpayers, bear the cost of bad investments.

Creditors’ rights

There is also concern that bankruptcy would violate the contractual rights of creditors. Chapter 9, which allows states to authorize their public corporations and municipalities – but not the states themselves – to file for bankruptcy, has been criticized in recent years for violating creditor priorities. For example, in the recent Detroit bankruptcy, creditors took substantial haircuts while public pensions and government services emerged largely unchanged. Puerto Rico’s recent actions suggest that it would attempt to follow suit.

For this reason, PROMESA takes an alternative approach. It sets up a court-supervised bankruptcy structure, but it gives the oversight board full authority over the restructuring process and mandates that the board respect the “relative lawful priorities or lawful liens” of creditors. For Puerto Rico even to file for bankruptcy, five of the seven board members must approve the decision. Additionally, the supervising court can approve a restructuring plan only if the plan is feasible and “in the best interests of creditors.” This requires that creditor outcomes be as good in bankruptcy as they would be outside of it. Once again, this approach puts a great deal of trust in the board, and some on the right question whether this trust is warranted.

There is also concern that the stay of litigation or the bankruptcy provisions in the bill will be challenged by creditors as an unconstitutional taking. Given the unique nature of the stay, it is most at risk, but it is unclear what, if any, compensation such a taking could demand. As for the post-hoc imposition of bankruptcy, Congress alters creditors’ rights every time it amends the bankruptcy code. It is unlikely to be viewed as unique here. And the “best interest of the creditors” standard adjudicated by the court should ensure that the creditors’ potential returns are not decreased by bankruptcy, eliminating any potential taking.

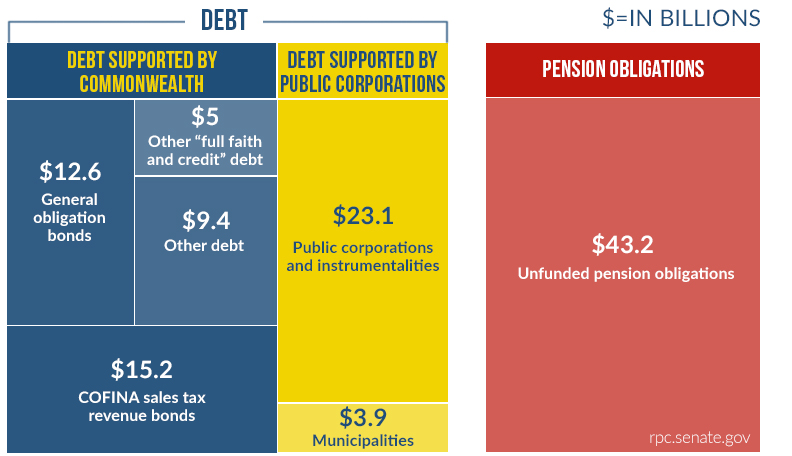

Pension obligations

PROMESA exposes Puerto Rico’s three pension systems to restructuring, which has caused seven of the nation’s largest labor unions to oppose the legislation. Puerto Rico’s pension systems present a $43 billion unfunded obligation. The pension systems have no assets and will be entirely pay-as-you-go by fiscal year 2018, at which point pension payments will draw more from the general fund than debt service obligations. PROMESA offers Puerto Rico an opportunity to make these obligations manageable, but restructuring is not automatic. The oversight board will control if and how pensions are restructured, and there is concern that a board appointed by the president, even if majority Republican, would not take on this challenge.

“It’s pretty clear a pay-as-you-go Puerto Rico pension system is no more sustainable than Puerto Rico’s debt.” – Senator Orrin Hatch, 04-07-2016

“Super 9” and contagion

There is also controversy surrounding which debts should be subject to bankruptcy. Puerto Rico’s debt was issued by a variety of institutions with varying payment sources and levels of protection. Constitutionally protected general obligation bonds are at the top of this hierarchy, followed by a variety of bonds issued or guaranteed by the commonwealth, such as COFINA bonds, which have a dedicated stream of tax revenue. Next to these are a variety of debts issued by public corporations and other instrumentalities.

Under traditional Chapter 9, the debt issued or guaranteed by the commonwealth, such as general obligation bonds, would not be subject to bankruptcy. Because of the complexity of the debt structure and the commonwealth’s role in supporting a majority of Puerto Rico’s obligations, PROMESA exposes every type of debt to potential restructuring in bankruptcy. Some are concerned that this change would set a precedent for extending bankruptcy access to state governments under Chapter 9 of the bankruptcy code – this is the so-called “Super 9.”

There are several reasons to discount this concern. PROMESA’s bankruptcy provisions work only with the supervision of an oversight board. This is something Congress could never impose on a sovereign state. States have repeatedly expressed their disinterest in Super 9, and it is unclear if Super 9 would be constitutional.

Some critics also argue that extending bankruptcy to Puerto Rico’s general obligation debt would disrupt the broader municipal bond market. While it’s difficult to predict how markets will respond, the market already has priced much of the deterioration in Puerto Rico’s finances into bond prices, and most market participants should recognize Puerto Rico’s unique situation. Ultimately, a July 1 default on Puerto Rico’s general obligation debt could be even more disruptive to markets.

Creditor collective action

PROMESA also creates a structure through which a two-thirds majority of creditors could agree to a restructuring plan that would bind all creditors, including those that did not agree to the restructuring. This is a novel structure in the U.S. but reflects “collective action clauses” that have been incorporated into sovereign debt issuances in Europe recently to address hold-out creditors in restructurings.

These collective action provisions would work parallel to the bankruptcy provisions and would be voluntary. Like the bankruptcy provisions, the creditor collective action would retroactively change creditors’ rights, but it potentially raises constitutional objections not raised by bankruptcy, as it operates without the precedent on which the bankruptcy provisions rely.

Pro-growth reform

PROMESA also includes several provisions to encourage economic growth. It permits the government to lower the island’s minimum wage for newly hired workers up to age 25 to $4.25 an hour for as long as four years. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has noted that applying the $7.25 federal minimum wage to Puerto Rico provides a “potentially strong disincentive for firms to expand their hiring of young workers.” Puerto Rico’s own hired consultant has repeatedly recommended lowering the island’s minimum wage.

PROMESA exempts Puerto Rico from the Department of Labor’s new overtime rule until the comptroller general of the United States assesses what effect the rule would have on Puerto Rico. The rule will significantly raise the annual salary threshold under which workers generally qualify for time-and-a-half pay when working more than 40 hours in a week. The government of Puerto Rico requested an exemption from the rule.

PROMESA also creates a revitalization coordinator to speed up the permitting process for critical projects on the island; requires a GAO report on utilization of the Small Business Administration’s HUBZone program; and establishes a congressional task force on federal impediments to economic growth in Puerto Rico.

Next Article Previous Article