Six Myths About the NSA Metadata Program

- The Supreme Court has made clear that acquisition of telephone metadata is consistent with the Fourth Amendment.

- There is oversight of this program by all three branches of government.

- Terminating the program would be a policy choice to eliminate this intelligence tool in a time of war against Islamist terrorists.

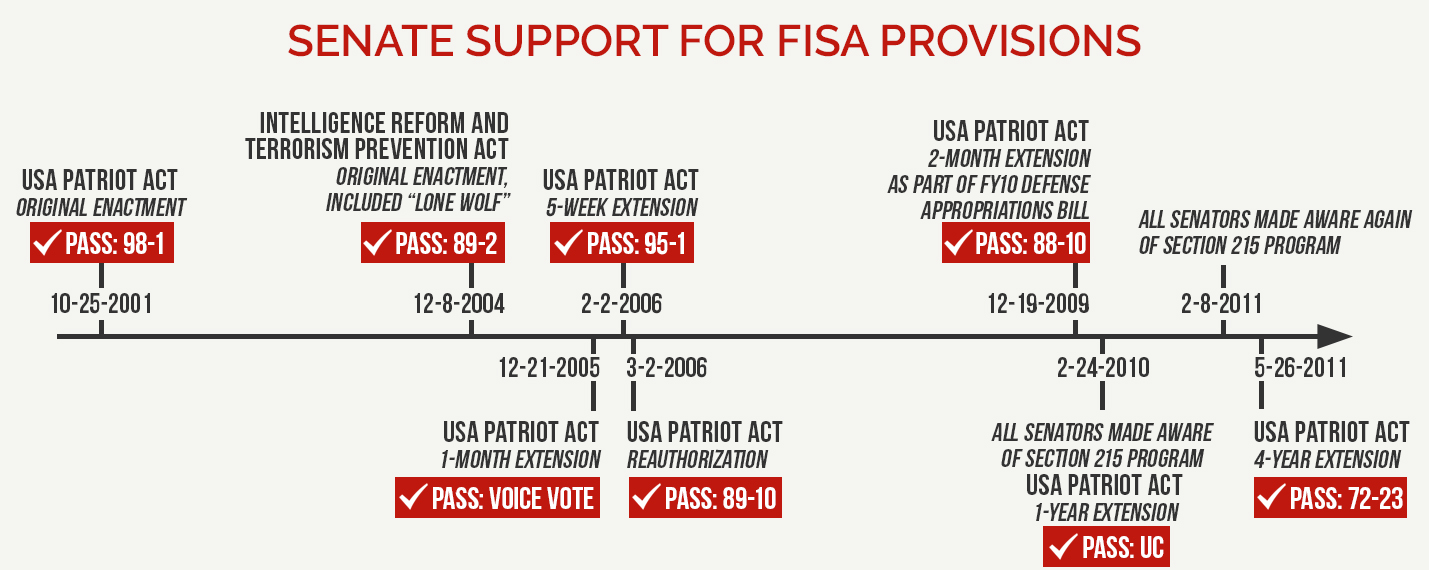

On June 1, three provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act expire – business records; roving wiretaps; and the “lone wolf” provisions. Since the original passage of the USA PATRIOT Act, the business records provision has been approved multiple times by the Senate. The amendments made to FISA by Patriot Act section 215 serve as the statutory basis for the NSA metadata telephone records program.

Myth 1: The telephone metadata program is unconstitutional.

Fact: The Supreme Court has said that people do not have a Fourth Amendment-protected interest in the numbers they dial on their phones. It is strictly a policy choice whether to eliminate a counter-terrorism intelligence tool in a time of continuing war against al-Qaida and an expanding war against ISIL.

The Fourth Amendment protects against “unreasonable searches.” A search occurs when the government intrudes upon “a reasonable expectation of privacy.” The Supreme Court has noted “that a person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties.” The court has also squarely determined that a person does not have a Fourth Amendment-protected privacy interest in the numbers he dialed on his phone. A person making a telephone call knowingly conveys to a third party, i.e., the telephone company, the number he is calling so the telephone company can complete the call and maintain a record of it for billing purposes. When the government acquires these records from a phone company, a search has not taken place for constitutional purposes.

Myth 2: The quantity of data acquired in the metadata program makes it unconstitutional.

Fact: The quantity of data acquired by court order has no bearing on the constitutional analysis.

The Fourth Amendment protects against “unreasonable searches.” For that protection to apply, a search must actually occur; and the third-party doctrine makes clear that a search has not occurred in this instance. Reasonable expectations of privacy do not have anything to do with the quantity of phone records obtained. The records do not involve content of the call. Given the type of information covered, and the manner in which the government acquires it from a third party, it does not matter whether the government acquires one telephone record from a phone company or, many days’ worth of records concerning many people. Again, for constitutional purposes, a search has not taken place.

Myth 3: A recent Supreme Court ruling requires a warrant to search phone data.

Fact: The Supreme Court ruling last year had nothing to do with the metadata program.

When a law enforcement officer makes an arrest, he can, without a warrant, make a search for limited purposes, namely for officer safety or to protect against evidence being concealed or destroyed. The Supreme Court ruled last year that if an arresting officer seizes the suspect’s cell phone in the course of an arrest, a warrant is required to review it.

Again, for the Fourth Amendment to apply, a search must actually take place. The court in this case specifically said that its decision does not “implicate the question whether the collection or inspection of aggregated digital information amounts to a search under other circumstances.”

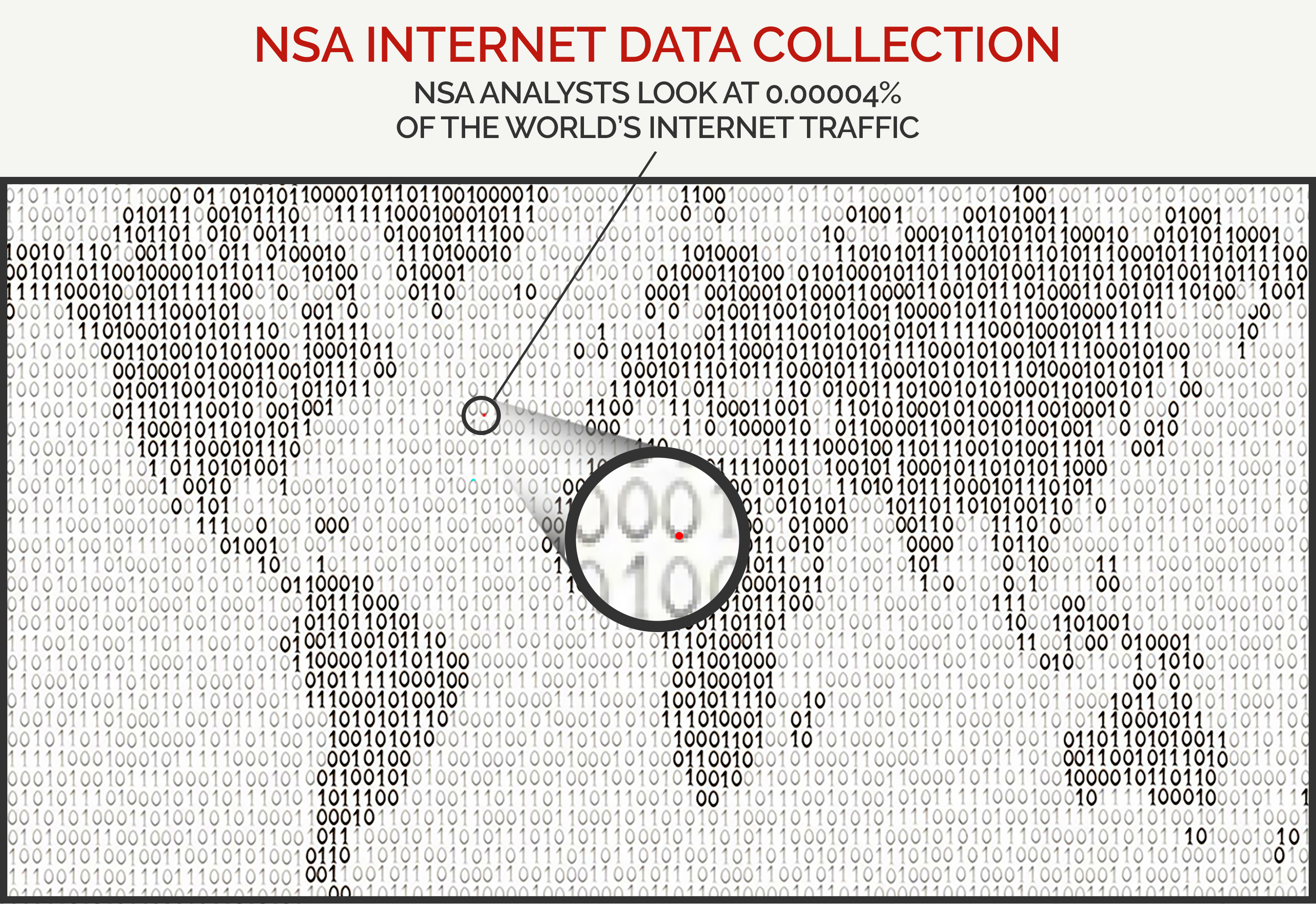

Myth 4: The metadata program is a massive intrusion into privacy.

Fact: This program actually provides more protection than analogous governmental acquisition of similar data.

Every day the government subpoenas third parties to produce a wide variety of business records, such as credit card statements, bank statements, and hotel bills. These subpoenas have little judicial review and no congressional oversight.

In contrast, there is significant oversight of the metadata program by all three branches of government:

- Judicial: The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court must issue an order authorizing this program every 90 days. The government files monthly reports with the court on how the program is carried out.

- Executive: NSA and the Department of Justice National Security Division are jointly responsible for monitoring NSA compliance with court orders covering this program.

- Legislative: Using the numerous reports it receives from the executive on this matter, as well as its own oversight investigations, congressional committees have robust oversight of this program. The Senate Intelligence Committee has said “a central focus” of its oversight has been over this particular program.

Myth 5: The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court is a “secret court” that is beyond review.

Fact: While the proceedings of the FISC are conducted in a secure, confidential manner, the judges themselves have sworn to protect the Constitution of the United States. The court consists of 11 U.S. District Court judges who are appointed by the Chief Justice of the United States and tasked with reviewing applications to surveil foreign intelligence targets. The director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts described the work of the FISC as that involving “applications in which experienced judges apply well-established law to a set of facts presented by the government – a process not dissimilar to the ex parte consideration of ordinary criminal search warrant applications.” A review court also ensures that the FSIC’s denials are done consistent with the law. This review court is composed of additional federal district or circuit court judges designated by the Chief Justice.

Myth 6: The metadata program has not stopped one attack.

Fact: Mike Morrell, the former acting director of the CIA and member of the President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies, has written: if this program had “been in place more than a decade ago, it would likely have prevented 9/11.”

The Congressional Joint Inquiry into the 9/11 attacks noted “NSA’s cautious approach to any collection of intelligence related to activities in the United States.” It said that a “gap” had developed in the coverage of communications coming in or out of the United States and foreign countries. It explained “this gap was potentially very damaging in the case of Khalid al-Mihdhar during the period in early 2000 when he was in the United States.”

President Obama has explained what this meant. Khalid al-Mihdhar, one of the 9/11 hijackers, was in the United States making phone calls to a known al-Qaida safe-house in Yemen. NSA saw the call but could not tell it was coming from inside the United States. As President Obama explained, the metadata program was designed to address this gap.

When Senator Feinstein was chair of the Intelligence Committee, she said:

“I strongly believe that the telephone call records program under the Section 215 Business Records provision reduces the chance of another 9/11-type attack on our homeland. In fact, the call records program has played a role in stopping roughly a dozen terror incidents in the United States. … To end the program at this time will substantially increase the risk of another catastrophic attack on the United States.”

The metadata program also provides value in assessing whether any foreign plots have a U.S. connection. If a terrorist plot is broken up overseas, this program can contribute to an investigation into whether the terrorists involved in that plot have been in contact with anyone inside the United States. That effort becomes far more cumbersome in the absence of this program.

Next Article Previous Article