Practical and Legal Problems with D.C. Statehood

KEY TAKEAWAYS

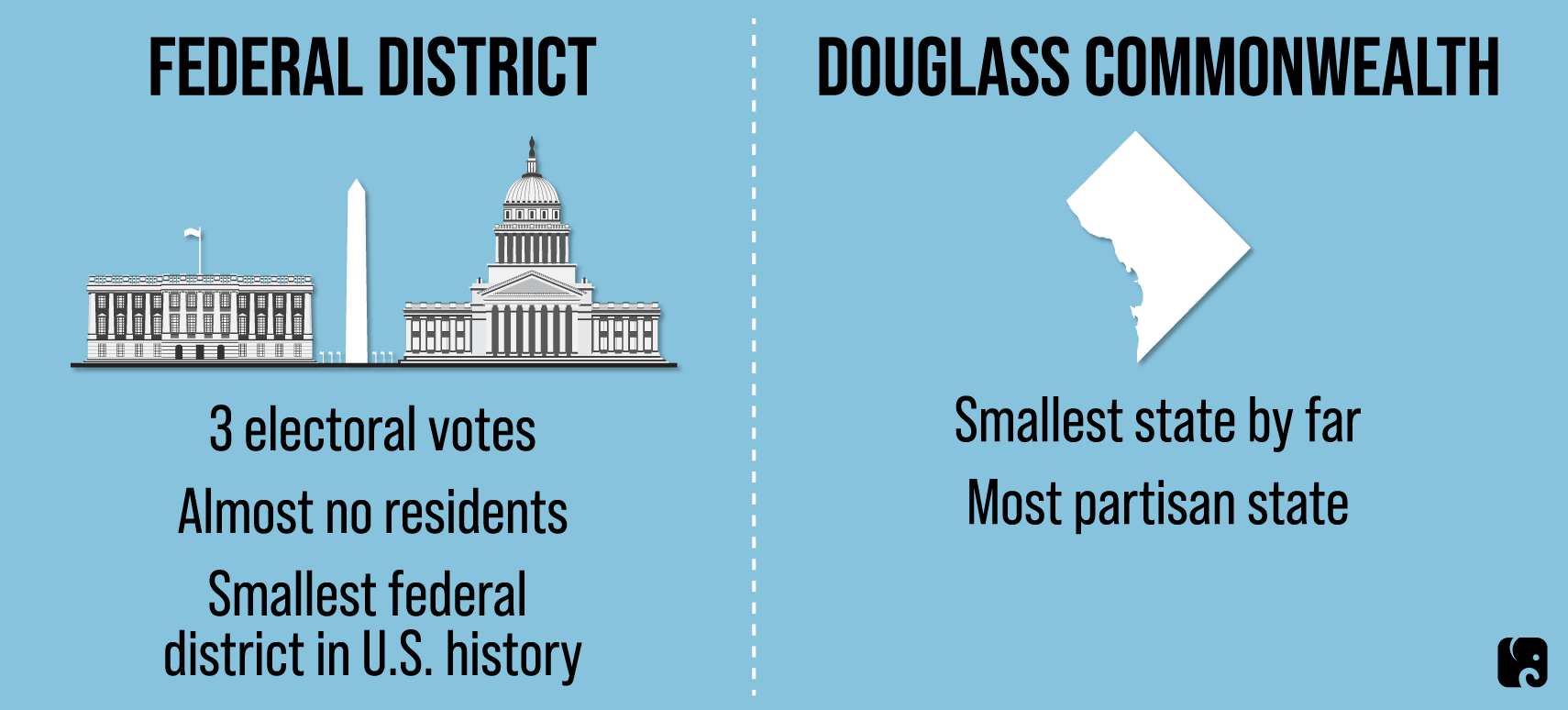

- Democrats in the House and Senate have proposed granting most of the land in the District of Columbia to a new state, to be called “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth.”

- The remaining federal District of Columbia would still have three electoral votes, with the president and his family potentially being the only voters awarding those votes.

- The plan would provoke thorny constitutional issues and create a new state very different from current states.

In the push to create a state unlike any other in the union, Democrats have ignored practical and legal problems that would burden the district and the electoral system as a whole. Because a constitutional amendment would be necessary to grant D.C. itself statehood, the current plan Democrats will vote for in the House this week would give most of the land in the current district to a new state, to be called “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth.” The remaining District of Columbia would be tiny, comprising several federal buildings, including the Capitol and White House.

Bizarre Aspects of a D.C. State and the Leftover District of Columbia

The state that would emerge under the current Democratic plan would be constitutionally vexing and highly unusual in many ways. Judging by recent election results, it would be by far the most partisan state in the country, and if its legislature reflected the current city council, it would be the only state with no Republican elected officials anywhere in the state government. Meanwhile, the federal district left over after the creation of a D.C. state would potentially award the president and his family as many votes in the Electoral College as the state of Vermont. Even honest proponents of D.C. statehood acknowledge that there is currently no plausible solution to some of these problems.

The Democratic Plan for D.C. Statehood

The District of Columbia is a creation of the Constitution, which limits what Congress can do to change its status without a constitutional amendment. Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 of the Constitution establishes that Congress has “exclusive” legislative power over “such District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States.”

Because the Constitution is so clear on this point, a constitutional amendment would be required to actually make the District of Columbia, as currently established, a state. Given the implausibility of a constitutional amendment on this point, Democrats in Congress have a different plan for D.C. statehood.

The plan would not technically give D.C. statehood. Rather, it would create a new state, to be named Washington, Douglass Commonwealth, out of a land grant from the federal government consisting of most of the current District of Columbia. Congress would shrink the federal District of Columbia to encompass only a few federal government buildings, such as the Capitol, the White House, and the Supreme Court.

Constitutional Arguments

By avoiding making the seat of the federal government a state, the Democrats’ plan sidesteps the need for a constitutional amendment to allow D.C. statehood. But in doing so, the plan creates new constitutional questions.

The Constitution outlines how land can enter the possession of the District of Columbia − “cession of particular states” − but not how land can leave it. While this might seem to means Congress can give the land back, similar provisions in the Constitution regarding statehood raise some doubt. For instance, the Admissions Clause gives Congress the power to admit new states but no power for expulsion or secession. The Supreme Court held in 1868 that once a state enters the union, the relationship is “indissoluble.” In that vein, some legal scholars have contended that just as the Constitution provides a way for states to enter but not leave the union, the Constitution provides a way for land to enter the district but not to be given away.

Opposing this legal view is the fact that in 1846 Congress granted back the land ceded by Virginia to form the original District of Columbia. That granting back of land, technically termed a “retrocession,” was challenged in the Supreme Court in 1875 by a resident of Alexandria seeking to avoid paying taxes to Virginia. The Supreme Court did not rule on the constitutionality of retrocession in order to resolve the case but left the retrocession in place. Observers over time have not agreed that the matter was settled. President William Taft believed retrocession was unconstitutional and wanted, in 1909, to have the Virginia land returned to the district. In theory, if the Supreme Court now held that land could not leave the district in order to form the Douglass Commonwealth, it could also call into question the legality of the retrocession, even though it has been accepted as fact for 175 years.

Another question arising from the Democratic plan is the constitutional prohibition on forming new states from the jurisdiction of any other state without the consent of the legislatures of the states concerned. The land constituting the current District of Columbia was granted by Maryland, so some legal scholars have argued that Maryland would have to consent to the land being granted to a new state. Others argue that Maryland permanently relinquished its claim to the land with its grant to the federal government. Either way, the Supreme Court likely would have to clarify the status of such land grants in a future case if the Democrats’ plan for D.C. is implemented.

Finally, the 23rd Amendment creates bizarre issues with the Electoral College votes for the hypothetical shrunken federal District of Columbia. The amendment, ratified in 1961, grants the district no more electoral votes than that of the smallest state in the union, which is currently three electoral votes. The votes do not depend on the size of the district. Under the Democrats’ plan, the residents of the new, smaller district would likely only be the president and the president’s family living in the White House. The first family would effectively get three electoral votes. Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution provides that no person “holding an office of trust or profit under the United States” shall be appointed an elector. This term includes the president. So, if a president lived alone in the White House, it is possible that no residents of the district could actually serve as electors.

The current version of the Democrats’ bill for D.C. statehood calls for expedited procedures to consider repealing the 23rd Amendment, but that repeal would require ratification by three-quarters of the states. Such a large number of states voting for ratification would require both red and blue states to ratify, and one of the political parties would be sacrificing a guaranteed three electoral votes in the next presidential election.

A New Kind of State

The State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth would be unusual in many respects, presenting new questions about how states can or should function. The average U.S. state’s area is about 76,000 square miles. Rhode Island, the smallest state, is 1,545 square miles. Washington, Douglass Commonwealth would be 68 square miles, less than a twentieth the size of Rhode Island.

The new state also would be by far the most partisan state in the union. The most partisan result in the 2020 presidential election among current states was Donald Trump receiving 70% of the Wyoming vote. By contrast, Joe Biden received 93% of the vote in D.C. There are currently no Republican elected officials in D.C., and if D.C. became a state and its legislature reflected the current city council, it would be the only state government where one of the two major U.S. political parties holds no elected office.

Next Article Previous Article