Medicare at 50: In Urgent Need of Reform

-

Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law 50 years ago. Unfortunately today the programs are on an unsustainable path and need reform.

-

The president has failed to lead on entitlement reform: Obamacare cut Medicare, using the savings to pay for new and expanded entitlements rather than shoring up the program.

-

There have been successful reforms to parts of Medicare that can provide a roadmap for broader reform of the program.

The United States confronts substantial long-term fiscal challenges, including a federal debt that now exceeds annual economic output and that is up $7.7 trillion since President Obama took office. The current path of federal spending will hamper innovation and cripple future economic growth. Medicare, which provides important financial protection for seniors, is the main contributor to the unsustainable trajectory of federal spending.

Without Medicare reform, Americans will need to accept massive spending cuts to areas such as defense, Social Security, and infrastructure spending; sizeable tax increases; or large Medicare cuts that would harm seniors and the disabled. President Obama has failed to lead on entitlement reform, choosing instead to expand entitlements through Obamacare.

Medicare Drives Increased Health Care Spending

On July 30, 1965, President Johnson signed Medicare and Medicaid into law. At the time, the federal government projected Medicare’s inflation-adjusted cost would reach $12 billion in the year 1990. By 1990, actual Medicare expenditures were $111 billion – more than nine times as high as the original projection.

Health care spending exploded after the program was created. In 1966, hospital expenditures jumped 22 percent from the previous year, and they rose an average of 14 percent over the next five years. Research shows that Medicare’s rapid growth was not a result of the overall increase in health care costs, but rather that Medicare was largely responsible for the explosion in overall health care spending. According to a 2007 study, at least 40 percent of the five-fold increase in real per capita health spending between 1950 and 1990 was due to “the introduction of Medicare [which] is associated with an increase in treatment intensity, as measured by hospital expenditures per day.”

Medicare’s Unsustainable Path

Today, Medicare consists of four separate parts. Part A provides hospital insurance, paying for inpatient care in hospitals and skilled nursing facilities. Part B provides medical insurance, covering doctor services and general outpatient care. Part C is Medicare Advantage, a private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare that is optional for seniors. Part D is the program’s prescription drug component.

On July 22, the trustees for the Medicare program released their annual report on the status of the program’s finances. In 2014, Medicare covered nearly 54 million people – 45 million aged 65 and older and nine million with disabilities – and spent $613 billion, about 3.5 percent of the nation’s total economic output. Average 2014 spending per beneficiary equaled $12,179, up 2.3 percent from 2013. This was the largest increase in three years, but lower than historical Medicare spending growth. Based on the slowdown in Medicare spending growth, the trustees assume “a substantial long-term reduction in per capita health expenditure growth rates relative to historical experience.”

Medicare has three main funding streams: general taxes; payroll taxes; and beneficiary premiums. In 2014, 42.4 percent of Medicare’s total income came from general revenue, 38.8 percent came from payroll tax revenue, 13.7 percent came from premiums, and 5.1 percent from other sources. The 2.9 percent payroll tax on earnings, split between the employer and worker, finances most of Part A. Obamacare added an additional payroll tax on earnings above $200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for married couples.

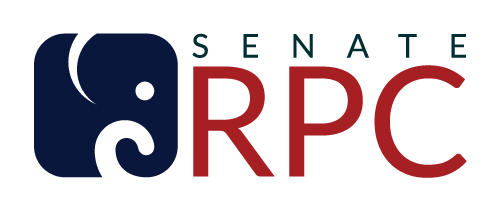

Despite the trustees’ assumption that the slowdown in the annual increases in health care spending will continue, they predict that Medicare expenditures will more than double over the next decade. By 2024, the trustees project that Medicare spending will reach nearly $1.24 trillion – an amount equal to about 4.3 percent of GDP. By 2040, when today’s newborns are beginning their careers, the trustees project that Medicare will equal about 5.6 percent of GDP under current law assumptions.

The trustees project that the Part A trust fund will become insolvent in 2030. At that point, incoming revenue is projected to cover about 86 percent of program expenditures, a percentage that declines over time. Part B and Part D can borrow as much as needed from general revenue to meet program expenditures.

While estimates of the trust fund’s condition are important, the trust fund itself is a Washington accounting mechanism. In 2000, the Office of Management and Budget explained, “[t]hese balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other trust fund expenditures – but only in a bookkeeping sense. These funds are not set up to be pension funds, like the funds of private pension plans. They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures. The existence of large trust fund balances, therefore, does not, by itself, have any impact on the Government’s ability to pay benefits.”

The percentage of Medicare’s expenditures funded by the payroll tax has declined significantly over time. In just the past 15 years, the percentage of total expenditures funded by the payroll tax has gone from 60 percent to less than 40 percent. By 2030, less than 30 percent of the program will be financed through the payroll tax.

The trustees also present an alternative scenario, which assumes that cuts in payments to providers, including Obamacare’s large reductions, do not occur. Many people consider the alternative scenario to be the more realistic scenario since Congress has repeatedly prevented Medicare cuts from taking effect in the past. Using the alternative scenario in which policymakers increase payment rates to Medicare providers above current law levels, the trustees project that Medicare’s costs rise to 6.0 percent of GDP in 2040 and to 9.1 percent of GDP in 2089. Medicare’s 75-year unfunded liability, the difference between expected spending and expected revenues, is $27.9 trillion under current law and $36.8 trillion under an alternative scenario. These unfunded liabilities amount to about $87,000 or $115,000 for each American today.

Although President Obama has failed to lead on entitlement reform, he has at least acknowledged the problem. In 2011 – more than one year after Obamacare became law – the president said: “if you look at the numbers, then Medicare in particular will run out of money and we will not be able to sustain that program no matter how much taxes go up. … [We] have an obligation to make sure that we make those changes that are required to make it sustainable over the long term.”

Medicare’s Structural Problems

Increased third-party payment and massive waste, fraud, and abuse

The vast majority of Americans’ health care is paid directly by third-party payers, mainly insurance companies or the government. Third-party payment for routine medical expenses means patients’ don’t see the cost of services, which leads to higher use and spending. Medicare enrollees currently have little incentive to reduce wasteful or unnecessary spending because the corresponding savings go to the government.

Before the introduction of Medicare, Americans directly paid about half of all medical expenses. Now, Americans only pay about 10 percent of all medical expenses directly. Most Medicare enrollees purchase supplemental insurance, which reduces their direct payment of services to virtually nothing. Since Medicare enrollees do not directly pay for the cost of services, providers have less incentive to find innovative or cost-effective ways of meeting their patients’ needs. Health care experts estimate that about 30 percent of Medicare spending does patients no good, and some of it is detrimental to their health.

Medicare price controls

Throughout Medicare’s 50-year history, the federal government has tried numerous types of price controls. All approaches have failed. Medicare’s traditional fee-for-service model, regardless of how bureaucrats determine the fees, has caused an overwhelming focus on quantity of services rather than quality of care.

In addition, the political process to determine payment rates is largely determined by interest groups. In a July 20, 2013, article the Washington Post reported that “[u]nknown to most, a single committee of the [American Medical Association], the chief lobbying group for physicians, meets confidentially every year to come up with values for most of the services a doctor performs.” The Post said, “the AMA’s estimates of the time involved in many procedures are exaggerated, sometimes by as much as 100 percent, according to an analysis of doctors’ time, as well as interviews and reviews of medical journals.” One former CMS administrator criticized the arrangement, stating that “[t]he concept of having the AMA run the process of fixing prices for Medicare was crazy from the beginning.”

Huge transfer of wealth

Medicare provides an enormous expected benefit to retirees and to people who are expected to retire in the next decade. For example, experts at the Urban Institute project that an average two-earner couple that retires this year will receive lifetime Medicare benefits of $427,000. This same couple paid lifetime Medicare taxes, in inflation-adjusted dollars, of $141,000 – meaning they can expect to receive three times as much in benefits as they paid in taxes. While this net benefit is likely overstated, since it assumes the program will continue paying full benefits when the trust fund is insolvent, it is clear that Medicare is an enormous and unsustainable transfer of wealth from younger Americans to older Americans.

Demographic Realities

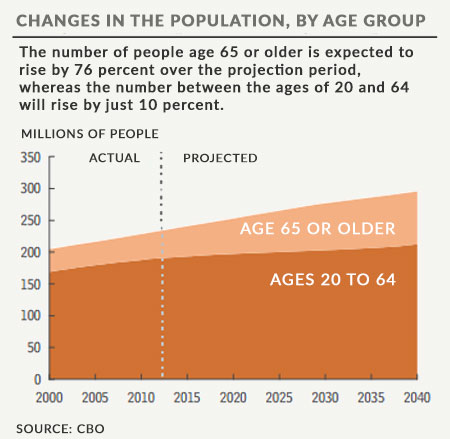

In addition to problems with Medicare’s structural design, the program’s pay-as-you-go finances present a serious problem because of dramatic demographic changes since 1965. Back then, life expectancy at age 65 was 13.5 years for men and 18 years for women. In 2015, life expectancy at age 65 has risen to 19.3 years for men and 21.6 years for women. This means that Medicare is now financing 5.8 years of additional medical services for men and 3.6 years more for women who reach Medicare’s normal eligibility age.

Fewer workers are paying taxes to finance the program’s growing expenses. In 1965, there were 4.5 workers for every Medicare beneficiary. Between 1980 and 2000, the number of workers per Medicare beneficiary was relatively stable at about four workers per beneficiary. This ratio began declining around 2000, with a much steeper decline after 2010 as the baby boomers began turning 65. In 2014, there were only about 3.2 workers per Medicare beneficiary. This ratio will continue to decline and is projected to reach 2.4 workers for each beneficiary in 2030, when the baby boomers will have all reached 65.

Obamacare Spent Medicare Savings and Created Medicare Rationing Board

Obamacare reduced Medicare payment updates, including for Medicare Advantage plans. CBO estimates that Obamacare’s Medicare provisions reduce program spending relative to pre-Obamacare law by $879 billion over the next decade. On paper, Obamacare’s Medicare changes, which include its increased Medicare payroll tax, extended the solvency of the Part A trust fund. Rather than using these savings to shore up Medicare’s failing finances, Obamacare largely diverting them to fund its Medicaid expansion and exchange subsidies.

The president’s health care law also created the Independent Payment Advisory Board, a body composed of 15 members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. It will have significant authority to reduce Medicare reimbursement rates in order to hit specified Medicare spending targets. The trustees project that Medicare’s growth rate will exceed the target growth rate for the first time in 2017, which means that in 2018 the IPAB would be required to submit proposals for how to cut Medicare.

The congressional committees of jurisdiction are expected to write legislation that will achieve the Medicare savings recommended by the board. If Congress fails to do so, the secretary of health and human services is required to implement the cuts suggested by the IPAB. By law, the IPAB is prohibited from making any recommendation that would ration care, increase taxes, change beneficiaries’ benefits or eligibility for coverage, or increase beneficiary premiums or cost-sharing. Of course, this task is impossible since lower provider payment rates, the IPAB’s only tool, will result in greater rationing of health care.

The IPAB is Obamacare’s attempt to double down on a price control system that has not controlled overall Medicare costs in the past and that is largely responsible for many of the inefficiencies in the health care system. The IPAB cuts will likely reduce access to certain medical treatments for many Medicare beneficiaries.

Success of Part D Provides Hope for Reform

In 2003, President George W. Bush signed the Medicare Modernization Act, which established Medicare’s prescription drug program. While Part D initially generated controversy because of its price tag, the program has proven to be one of Medicare’s success stories. The Part D program was developed on a model in which government’s assistance is delivered to the person and not Medicare’s traditional model of government fixing reimbursement rates and making payments to providers.

In the Part D program, the federal government subsidizes private coverage with a fixed amount and leaves insurers to compete on premiums and benefit design. In contrast with the huge cost overruns in traditional Medicare, Part D expenditures are nearly 40 percent lower than initial projections. Part D has had the additional benefit of lowering Medicare hospitalization rates by about four percent, generating annual savings to the program of approximately $13 billion in 2006 alone. Given the need for future reform to make Medicare fiscally sustainable and address its numerous problems, Part D offers hope that replacing Medicare price controls with market discipline may do the job.

Next Article Previous Article