Defense Budget Overview & Considerations

- The preamble of the Constitution says one of the purposes for the founding of the national government was to “provide for the common defense.”

- Secretary of Defense James Mattis testified last month: “no enemy in the field has done more to harm the readiness of our military than sequestration.”

- To remedy this, as Henry Kissinger has observed, “the United States should have a strategy-driven budget, not budget-driven strategy.”

WHERE WE ARE

The current Budget Control Act cap for all national defense discretionary spending (budget function 050) for fiscal year 2018 is $549 billion. The Department of Defense usually comprises 95.5 percent of all budget authority in this category.

The administration’s overall fiscal year 2018 defense budget request within the jurisdiction of the Senate Armed Services Committee was for $659.8 billion in discretionary spending, composed of:

- $574.7 billion for the Department of Defense base budget

- $20.5 billion for Department of Energy national security programs and the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board

- $64.6 billion for overseas contingency operations

The fiscal year 2018 defense authorization bill as reported out of the Senate Armed Services Committee authorizes $692.1 billion in spending, $32.3 billion more than the president’s request:

- $610.9 billion for the Department of Defense base budget

- $21 billion for DOE and DNFSB national security programs

- $60.2 billion for OCO

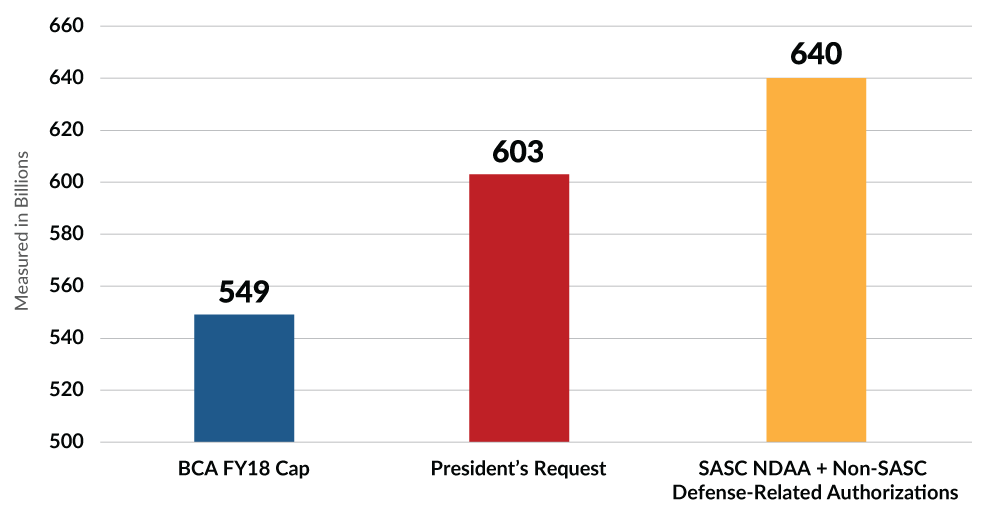

If defense-related authorizations outside the jurisdiction of the Senate Armed Services Committee are added to this in a way consistent with historic authorizations and the president’s request for this upcoming fiscal year, the base (excluding OCO) discretionary spending number for all budget function 050 would be approximately $640 billion. This compares to $603 billion for category 050 in the president’s request, and the BCA limit in fiscal year 2018 of $549 billion.

National Defense Spending (Budget Function 050)

HOW WE GOT HERE

-

The Budget Control Act created what became known as the “Super Committee,” which was directed to aid in the ultimate passage of legislation reducing the deficit by $1.2 trillion over 10 years.

-

When that effort failed, the automatic enforcement mechanisms of sequester and revised caps achieving similar savings were actuated.

-

With respect to the revised caps, defense spending was effectively cut by $54 billion each year starting in fiscal year 2013. Cuts to non-defense discretionary spending were less (generally around $37 billion each year).

-

As CBO points out, cuts to defense spending are “proportionately larger” than cuts to nondefense discretionary programs under the Budget Control Act.

-

The National Defense Panel Review of the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review described the ultimate result as defense spending being cut by almost one trillion dollars over 10 years ($937 billion) as compared to the fiscal year 2012 budget submission.

-

Limited relief from these drastic spending cuts has been given to the Defense Department in past fiscal years, but it has never amounted to full relief.

-

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (the fiscal cliff deal) lessened the amount of the defense spending cut for fiscal year 2013 by $12 billion ($24 billion split evenly between defense and non-defense). This increased spending was offset by lowering the spending caps in fiscal years 2013 and 2014, along with revenue changes affecting retirement accounts.

-

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (Ryan-Murray) raised the defense spending cap by $22 billion for fiscal year 2014, and $9 billion in fiscal year 2015. This relief was paid for by a mixture of fee increases and cuts to mandatory spending, namely a reduction in the growth of cost-of-living adjustments for certain military retirees, along with an extension of the sequester on certain mandatory spending. A military pension law in the 113th Congress extended mandatory sequestration through 2024.

-

The NDP noted this limited relief was helpful, but “nowhere near enough to remedy the damage which the Department has suffered and enable it to carry out its missions at an acceptable level of risk.”

-

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 did three main things for defense spending:

-

It raised the cap for defense spending by $25 billion for fiscal year 2016. (It raised the cap for non-defense spending by the same amount).

-

It set caps for defense (and nondefense) spending each for fiscal year 2017, raising them by $15 billion each.

-

It said OCO spending for budget function 050 (defense) was to be $58.7 billion in fiscal years 2016 and 2017 each.

-

This increase in base (non-OCO) discretionary spending of $80 billion over two years was offset with decreases in direct spending and certain revenue increases.

-

The effect of this agreement was to set a cap on national defense spending (budget function 050) of $548.1 billion and $551.1 billion for fiscal years 2016 and 2017 respectively.

-

CBO points out that base Department of Defense spending usually comprises 95.5 percent of all budget authority in this category.

-

The amount of base funding appropriated to the Department of Defense for fiscal year 2016 was $521 billion (including military construction).

-

As a point of comparison, when President Obama submitted his fiscal year 2012 budget request, the last budget request before the sequester and revised caps were implemented, the Department of Defense was projecting a budget of more than $600 billion in fiscal year 2016.

-

The amount of base funding appropriated to the Department of Defense for fiscal year 2017 is $523 billion (including military construction).

-

In addition to this, for fiscal 2017, the Department also received $82.4 billion in OCO (not including military construction), at

-

$61.8 billion in Title IX of the Defense part (Division C) of the omnibus,

-

$14.8 billion in Title X of the omnibus, and

-

$5.8 billion provided earlier in the year in Division B (the Security Assistance Appropriations Act of Fiscal Year 2017) of P.L. 114-254 (carrying the continuing resolution).

-

Of note, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 suggested an OCO limit for budget function 050 in fiscal year 2017 of $58.8 billion.

-

-

PRESIDENT OBAMA’S DEFENSE CUTS

-

President Obama’s desire to decimate defense spending predated the BCA. In his fiscal year 2012 budget request, the Department of Defense committed to cutting its own budget by $78 billion over the next five years. Two months later, in April 2011, President Obama announced his intent to seek an additional $400 billion in defense cuts over the next 12 years.

-

In effect, the Budget Control Act, aside from the automatic enforcement mechanisms of sequester and revised caps, substantially reflected the defense cuts President Obama was already planning.

- As the NDP noted, “prior to the BCA,” President Obama was already planning for $478 billion in defense cuts.

- This is consistent with Secretary of Defense Panetta’s description of defense spending cuts under the BCA, not counting the automatic enforcement mechanisms, as requiring “more than $450 billion in savings.”

-

The fiscal year 2012 Defense Department budget proposal had very modest nominal dollar increases for a decade. Secretary of Defense Gates described it as “a goal of holding growth in the base national security spending slightly below inflation for the next 12 years.”

EFFECT OF DEFENSE CUTS

-

Military officials and expert analysts have almost universally condemned the deleterious effect of these defense cuts.

-

In prepared testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 13 of this year, Secretary of Defense Mattis said “no enemy in the field has done more to harm the readiness of our military than sequestration.”

-

In prepared remarks to the Senate Armed Services Committee subcommittee on readiness, the vice chief of staff of the Army said that if the fiscal year 2018 Budget Control Act defense spending caps are adhered to, this would “increase the risk of sending under-trained and poorly equipped Soldiers into harm’s way.”

-

The vice chief of naval operations said in that same hearing that “funding reductions” are a contributing factor to the Navy overall readiness reaching “its lowest level in many years.” “Readiness has become the bill payer” for the “fiscal pressures imposed” by the BCA.

-

The vice chief of staff of the Air Force said funding issues contribute to Air Force readiness being at “a near all-time low.”

-

The assistant commandant of the Marine Corps said the Marines under the current funding structure “will experience increasingly significant challenges to the institutional readiness required to deter aggression and, when necessary, fight and win our Nation’s battles.”

DEFENSE SPENDING IS NOT THE DRIVER OF OUR DEBT

-

Independent analyses of the federal budget by CBO make clear the federal debt is primarily driven by entitlement spending.

-

Mandatory spending in fiscal year 2018 is expected to be more than $2.5 trillion, more than four times the amount expected to be spent on defense that year.

-

Spending on Social Security alone is projected to be close to $1 trillion in fiscal year 2018 ($988 billion). Adding in Medicare and Medicaid, those three entitlement programs alone are projected to cost more than $2.1 trillion in 2018, almost four times as much as the current defense spending cap for 2018.

-

Using its projection modeling rules, CBO estimates defense spending will be $762 billion in 2027, while all mandatory spending would amount to $4.3 trillion.

Spending Growth (outlays), 2018-2027

,-2018-2027.png)

-

CBO projects that discretionary spending as relative to the size of the economy will “significant[ly]” decline over the next 10 years but that decline is “more than offset” by the substantial growth in the cost of health care and social security entitlement programs, along with an increase in debt interest payments.

-

The defense budget should, of course, be subject to the same scrutiny as all other federal programs. But the fact remains that federal spending on defense is dwarfed by entitlements, and the difference will only grow over time unless steps are taken to reform the entitlement programs that are the biggest drivers of our debt.

-

Defense spending cuts account for fifty percent of the spending cuts required by the BCA automatic enforcement mechanisms. On the other hand, the true drivers of our debt, entitlement programs, took very little cuts, and nothing close to the structural reforms required for future solvency.

Next Article Previous Article