Debt Limit on Agenda Again

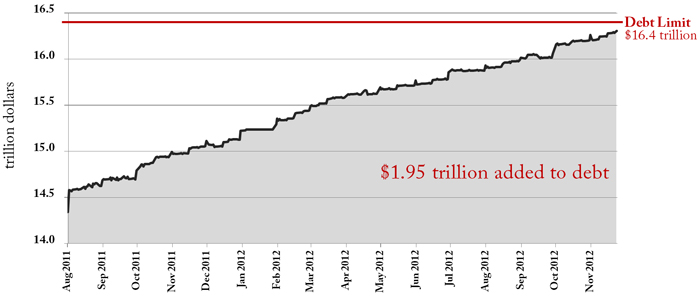

The Treasury Department recently announced that it expected the U.S. government to hit its debt limit of $16.394 trillion “near the end of 2012.” Treasury can take certain “extraordinary actions” to keep the debt limit from affecting U.S. government finances for a few weeks, but the President will need once again to ask Congress to raise the nation's debt ceiling in 2013.

The 2011 Debt Limit Increase

In 2011, Congress increased the debt limit by a total of $2.1 trillion in two separate increments:

- $900 billion in August and September 2011;

- $1.2 trillion in January 2012.

Taken together, this was the largest increase ever made to the debt limit. Democrats had sought to increase the debt limit without cutting spending or with minimal cuts, but Republicans pushed for spending cuts of $2.1 trillion to match the debt increase.

Debt Limit Approaching

The timing of hitting the debt limit in 2011 was pushed back several times. In January 2011, Treasury estimated that the limit would be reached between March 31 and May 16. In March, the estimate was moved to between April 15 and May 31. In April, Treasury settled on a specific day: May 16. On May 16, Secretary Geithner sent a letter to Congress announcing that he was taking extraordinary actions that would push off the final date for congressional action to August 2. President Obama signed the Budget Control Act raising the debt limit into law on August 2.

Treasury Actions to Delay Hitting the Debt Limit

The extraordinary actions used by Treasury are authorized by law and are limited. However, it is very difficult to determine the exact day that these extraordinary options will run out, and there is no guarantee that they will extend the deadline by the same amount of time they did in 2011.

Routine methods to avoid hitting the debt limit

Use cash balances. Treasury maintains cash balances with the Federal Reserve. Treasury can draw on this cash to pay obligations that would otherwise be financed with new borrowing. However, it must maintain an adequate balance in the Federal Reserve account because the Fed is legally prohibited from loaning the Treasury funds in the event of an overdraft.

Cash Management (CM) bills can be issued. CM bills are the Treasury’s method of borrowing cash for very short periods – usually just a few days at a time. When close to the debt limit, Treasury can use CM bills in a two step process that favors short-term borrowing over long-term borrowing. First, Treasury either reduces the overall amount it seeks to borrow via long-term securities auctions, or it actually delays those auctions by a few days or weeks (to allow time for the debt limit to be increased). Second, it replaces the lost borrowing with CM bills. Because this strategy involves altering regularly scheduled securities auctions and borrowing less money over a shorter time, GAO has said that it likely increases the long-term cost of borrowing money.

Extraordinary methods to avoid hitting the debt limit

Suspend issuance of SLGS securities. In 1969, Congress restricted the maximum yield that state and local governments could earn from investing tax-exempt bond proceeds (the goal was to reduce the risk that the state or local government might lose some of the proceeds of the bond). Established in 1972, State and Local Government Series (SLGS) securities are offered by Treasury to help state and local governments invest their bond proceeds in securities with a yield under the legal maximum. This Treasury action does not actually lower the debt subject to the limit. Since SLGS securities can be issued any day that a state or local government would like to purchase them, suspending their issuance temporarily halts Treasury borrowing in this particular program until after the debt limit is raised. This action is typically the first extraordinary one used when the government gets close to the debt limit.

Exchange FFB debt for debt subject to the limit. The Federal Financing Bank (FFB) essentially acts as the financing agency for many federal departments and agencies that incur debt or issue loan guarantees. Up to $15 billion in FFB debt is not subject to the statutory debt limit. Treasury has the authority to swap some debt subject to the limit in exchange for FFB debt. This action actually lowers overall debt subject to the limit.

Suspend G-Fund investments. The Thrift Savings Plan, the federal employee retirement program, invests a certain portion of its employee and employer contributions in Treasury securities. Treasury can suspend this investment when close to the debt limit. This action ensures that no new debt is incurred in this program until after the debt limit is increased. After the limit is raised, Treasury is legally obligated to repay lost interest on these uninvested funds.

Suspend ESF investments. The Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) holds several types of assets, one of which is U.S. dollars. ESF often invests its excess dollars in Treasury securities. By suspending ESF investments, Treasury prevents another program from increasing the debt subject to the limit.

Extraordinary methods used when the debt limit has been reached

Suspension and disinvestment of CSRDF investments. The Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF) is a trust fund for federal retirement that invests in Treasury securities. This option is only available to Treasury when the debt limit has been reached. Once this occurs, Treasury can notify Congress that it is declaring a “debt issuance suspension period.” This allows Treasury to take two separate actions: (1) suspend new CSRDF investments in Treasury securities; and (2) actually disinvest some Treasury securities held by the CSRDF. These actions do not have to be taken jointly but have been used together since 1996.

Other methods outside of Treasury’s authority. Congressional action is required to allow any additional borrowing if all Treasury options have been exhausted. For example, Congress once passed a measure that allowed the March 1996 Social Security benefits to be paid with borrowing that was temporarily designated as not subject to the debt limit.

America’s current fiscal path is unsustainable, with four debt limit increases in the last four years:

- February 17, 2009 (P.L. 111-5): $789 billion

- December 28, 2009 (P.L. 111-123): $290 billion

- February 12, 2010 (P.L. 111-139): $1.9 trillion

- August 2, 2011 (P.L. 112-25): $2.1 trillion

The fiscal cliff and the debt limit both illustrate the need for strong reform of entitlements and other federal spending to help control deficits and the debt. Presidential leadership is needed for this effort to succeed.

Next Article Previous Article