Closing the Digital Divide

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- There is a significant “digital divide” between urban areas that have widespread access to high-speed internet service and rural areas that often don’t; reasons include terrain, population density, demography, and other market factors.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the serious consequences of many Americans having limited access to reliable high-speed internet at home.

- Senate Republicans have prioritized closing the digital divide and passed legislation to improve the accuracy of broadband availability maps.

During the coronavirus pandemic, broadband internet in the home has been critical to full participation in commerce, education, and other essential components of American life. Broadband, a generic term for high-speed internet, increasingly is viewed as a basic infrastructure. As more of our day-to-day lives have moved online and things like telework, telemedicine, and remote learning became more prevalent, the speed of the internet has become more important. People who may previously have been able to get by with slower internet connections like dial-up service are at a growing disadvantage and at risk of being left behind.

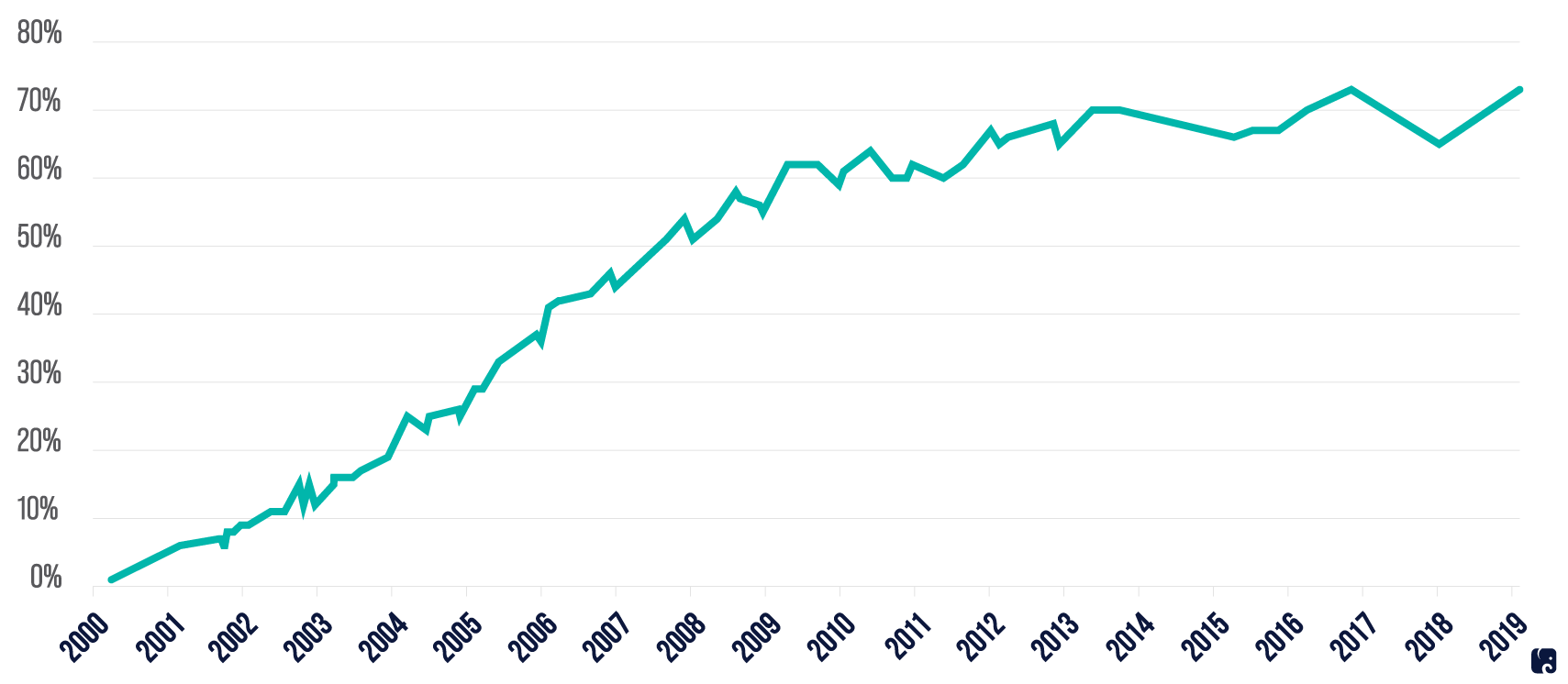

Share of Americans with Home Broadband Has Grown Rapidly

Source: Pew Research Center

While all levels of government and the private internet service providers have tried to ensure Americans do not lose service during the pandemic, some people still lack reliable access to high-speed internet. Senate Republicans have made improving this access a priority in the 116th Congress: passing legislation to ensure accurate broadband availability maps; conducting focused oversight of the Federal Communications Commission; and authorizing millions of dollars in funding for broadband infrastructure in underserved areas.

Coronavirus exposes consequences of digital divide

In a single generation, high-speed internet at home has gone from novelty to necessity. Since 2010, the FCC has recommended that universal access and adoption of broadband be a “national goal.” At the time, broadband was defined as a connection that could download information at a speed of four megabytes per second. The standard has risen over the past decade, and now broadband is considered to be at least 25 Mbps, with minimum upload speeds of 3 Mbps.

The term “digital divide” is often used to describe the gap between those who have access to broadband, and those who do not. According to the FCC’s 2020 Broadband Deployment Report, 22% of Americans in rural areas and 27% of Americans in tribal lands lacked coverage from fixed terrestrial 25/3 Mbps broadband, as compared to only 1.5% of Americans in urban areas. There are a few reasons for this urban/rural divide, including the terrain of an area, population density and demographics, and other market factors. These factors combine to discourage private-sector companies from making the investments to build the infrastructure for modern broadband. The companies often do not get the return on investment they need to justify building broadband in some areas of the country.

In addition to the urban/rural divide, some American families technically have access to broadband in the home, but may have trouble affording the service. In the 2017 Current Population Survey, one-third of homes with school age children that lack internet said the cost was their main reason. According to a 2018 Pew Research Center poll, 35% of teens in households with an annual family income below $30,000 lived in households without high-speed internet. In contrast, only 6% of teens living in households with a family income of at least $75,000 lacked broadband at home.

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed the serious consequences of many Americans having limited access to high-speed internet at home. When much of America’s schooling moved online in March, children without broadband at home were suddenly in danger of falling even further behind at school. In one Kansas City, Missouri, school district, up to 40% of students in grades 3-12 were not logging in when they were scheduled to. Officials cited lack of internet access as a chief reason. With some libraries and other common public sources of high-speed internet connections closed, people have found creative solutions. Two girls in California went viral on the internet after a photo was taken of them sitting outside a Taco Bell in order to use the free Wi-Fi to do their homework.

The fcc takes Action

The FCC has launched a variety of initiatives to expand broadband access across America. A key part of this effort is the Universal Service Fund. The universal service concept was begun in 1934 to help establish telephone service across America, including in remote, rural, and other areas where the cost of providing service was high. Today the fund covers a number of programs aimed at boosting broadband adoption.

One prominent USF program is the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund. Through this fund, the FCC plans to provide $20.4 billion in funding over two phases to bring broadband to rural homes and businesses. In the first phase, which begins in October, the FCC plans to award $16 billion to companies that present sustainable business cases for deploying broadband in areas with no service.

In addition to FCC programs, the Rural Utilities Service at the Department of Agriculture provides loans and grants to rural service providers for broadband connectivity and infrastructure development in rural areas. In fiscal year 2019, Congress appropriated more than $634 million to various programs financed by the RUS.

republicans prioritize closing the digital divide

Senate Commerce Committee Chairman Roger Wicker has noted, “To close the digital divide, we need accurate maps to show where there is broadband service and at what speeds it is being offered.” This kind of mapping has proven extremely difficult. The current National Broadband Map is maintained by the FCC based on information from service providers. One chief criticism has been that it can overstate availability because data is collected at the census block level, and a block is considered “served” if there is broadband anywhere in it. This can cause problems in rural areas, which have large census blocks, since regulators use the map to determine eligibility for some programs aimed at closing the digital divide.

Senate Republicans have taken steps to improve the accuracy of broadband availability maps. In March, President Trump signed into law the Broadband Deployment Accuracy and Technological Availability Act. The bipartisan legislation requires the FCC to collect granular service availability data from wired, fixed wireless, and satellite broadband providers; sets strong parameters for service availability data collected from mobile broadband providers to ensure accuracy; creates a process for consumers, governments, and other groups to challenge FCC maps with their own data; and establishes a crowdsourcing process that will allow the public to participate in data collection.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act included increased funding for programs to help close the digital divide, including $200 million for the FCC to support telehealth services in rural communities; $100 million for an RUS broadband deployment pilot program; and $25 million to support rural distance learning. In addition, The CARES Act provided $16 billion to states, which can use the money to support broadband for remote learning, among other priorities.

In May, the Commerce Committee held a hearing on the state of broadband during the pandemic. The hearing examined the effect of funds provided through the CARES Act to support broadband initiatives and other legislative proposals to address the digital divide.

In August, Senator Wicker and Senator Tim Scott introduced the Connecting Minority Communities Act. The legislation would establish the Office of Minority Broadband Initiatives at the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. It also would create a pilot program to provide $100 million in grants to purchase broadband service and equipment in minority communities.

In June, Senators Wicker, Shelley Moore Capito, and Marsha Blackburn introduced the Accelerating Broadband Connectivity Act. The ABC Act would expedite the deployment of broadband service by providing incentives for companies participating in the FCC’s Rural Digital Opportunity Fund to fulfill their obligations faster.

Also in June, Senator John Thune introduced the Rural Connectivity Advancement Program Act. The legislation would set aside 10% of the net proceeds from spectrum auctions conducted by the FCC through September 30, 2022, for the construction of broadband networks in rural areas. It also would require the agency to consider the broadband needs of residents of tribal lands when allocating the funds.

Next Article Previous Article