A Down Payment on Health Reform

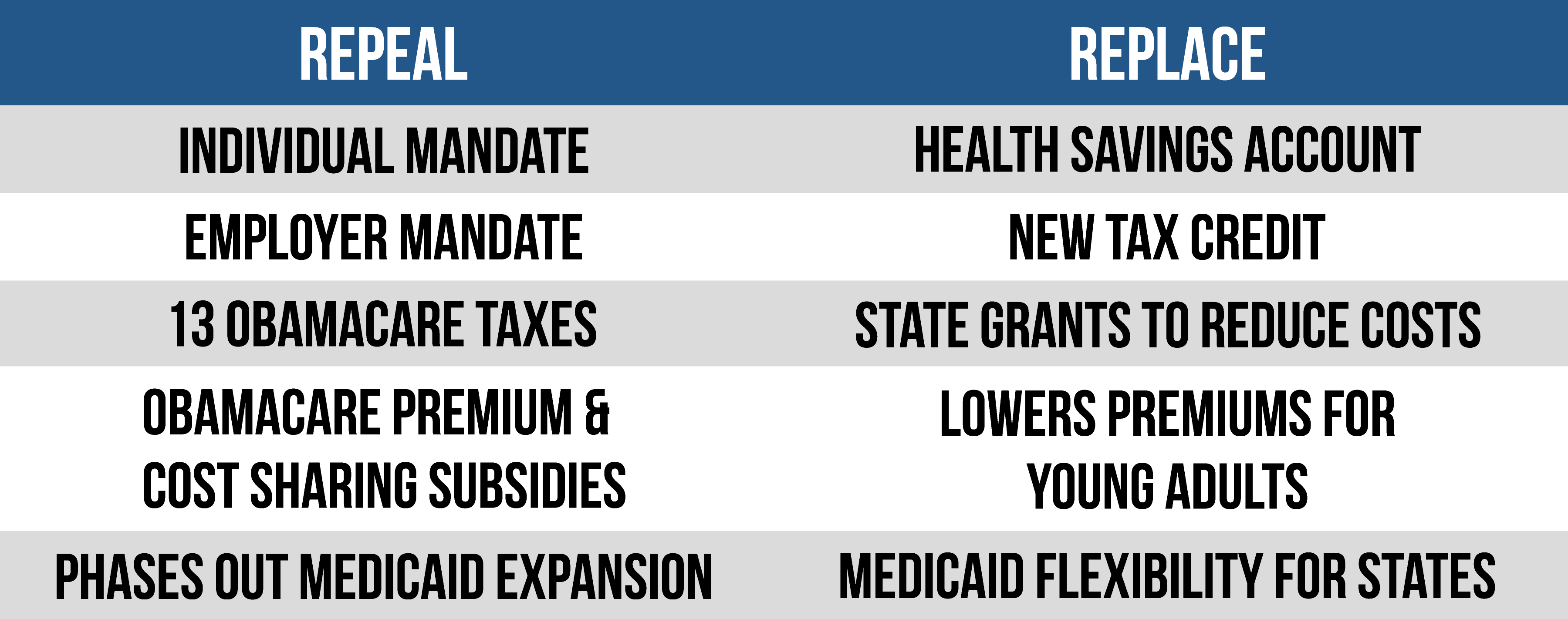

- The House plan repeals Obamacare’s tax increases, subsidies, penalties, mandates, and Medicaid expansion.

- This step forward will not be the end of the repeal and replace strategy, but it will start to bring Americans relief from the collapsing Obamacare system.

Keeping OUR PROMISE

After almost seven years of the Obamacare nightmare, the House has put together a plan that fulfills many of the promises made by Republicans to the American people. The American Health Care Act, constrained by rules in the Senate, repeals Obamacare’s main provisions and replaces them with better reforms. Among the House bill’s many provisions, it repeals Obamacare’s tax increases, subsidies, and Medicaid expansion. It also includes a new tax credit to help people purchase health coverage, Medicaid reforms, and the Patient and State Stability Fund. The Congressional Budget Office predicts that the bill will reduce Washington’s deficits by $337 billion over the next 10 years.

The American Health Care Act

REPEAL OF OBAMACARE’S TAXES

The bill eliminates or postpones 15 different Obamacare taxes.

Beginning in tax years after 2015, and applied retroactively:

- Individual mandate penalty is $0

- Employer mandate penalty is $0

Beginning in 2018:

- Repeal of the tax on prescription drugs

- Repeal of the 10 percent indoor tanning tax

- Repeal of the health insurer tax

- Repeal of the 3.8 percent net investment tax

- Repeal of the limit on deductibility of compensation for certain employees for health insurers

- Repeal of the exclusion of over-the-counter medicines from the allowable uses of tax-advantaged health accounts

- Repeal of the increase in the tax applied to purchases of disallowed products with tax-advantaged health accounts

- Repeal of the limit placed on employer contributions to flexible spending accounts

- Repeal of the 2.3 percent excise tax on medical devices

- Repeal of the elimination of the employer deduction for offering retiree prescription drug coverage

- Repeal of the increase in the amount of income that must be spent on medical expenses before a deduction is allowed

- Repeal of the 0.9 percent increase in Medicare payroll tax for higher-income earners

Delayed until 2025:

- 40 percent excise tax on high-cost employer health plans

Repeal of Obamacare’s subsidies

Obamacare’s premium tax credits, cost-sharing reduction subsidies, and small business tax credit are repealed in 2020.

In 2018 and 2019, the bill allows Obamacare’s subsidies to be used for catastrophic-only plans and used for qualified health plans offered off the exchanges. It explicitly states that subsidies cannot be used to purchase a plan with abortion coverage.

The bill also adjusts how the Obamacare subsidies are calculated for 2019. This makes them more generous for younger adults and requires older adults to pay a greater share of their income on premiums before subsidies kick in.

In addition, the bill repeals the limits placed on subsidy repayment for people who received an excess premium tax credit.

NEW REFUNDABLE TAX CREDIT

Beginning in 2020, the bill creates a new advanceable, refundable tax credit for people who are not eligible for coverage under a government program or are not offered employer-sponsored insurance. To receive the credit, a person must be a citizen or qualified alien and cannot be incarcerated.

The credit amounts vary by age:

- Under age 30: $2,000

- Between 30 and 39: $2,500

- Between 40 and 49: $3,000

- Between 50 and 59: $3,500

- Over age 60: $4,000

The credit is capped at $14,000 per family and will grow at the rate of the consumer price index plus 1 percent. The credit will begin to phase out at incomes above $75,000 for an individual and $150,000 for joint filers. The phaseout is gradual, decreasing by $100 for every $1,000 increase in income above the thresholds. The bill allows any excess credit to be deposited into a health savings account.

EXPANSION OF HEALTH SAVINGS ACCOUNTS

The maximum contribution for health savings accounts is nearly doubled. It is increased to the sum of the annual deductible plus the maximum out-of-pocket expenses permitted under a high deductible health plan. In addition, both spouses are able to make catch-up contributions, and HSA funds may be used to pay for qualified medical expenses incurred 60 days before the account is established. These changes begin in 2018.

FUNDAMENTAL MEDICAID REFORMS

The bill makes several changes to the Medicaid program. Most notably:

Phases out Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion. Beginning in 2020, the federal government will no longer pay the Obamacare enhanced payment rate for any new expansion population enrollees. States will be allowed to cover people earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, but any new enrollee after 2020 will be reimbursed at a state’s normal match rate. The Obamacare enhanced payment rate will only continue for expansion enrollees who were enrolled prior to 2020 and do not have a break in coverage.

Increases DSH payments. Beginning in 2018, Obamacare’s reductions in Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payments for states that did not expand Medicaid will be repealed. States that did expand Medicaid will have their DSH payments fully restored in 2020.

New safety-net funding. Provides $10 billion over calendar years 2018-2022, to non-expansion states to increase payments to Medicaid providers. Each state’s allotment of the $2 billion per year will be based on the number of residents below 138 percent of the poverty line in 2015, relative to the total number of people below this amount in all other non-expansion states. If a state expands Medicaid, it is no longer eligible for safety-net funding the following years.

Reforms Medicaid program payment to per-capita caps. Starting in fiscal year 2020, federal funding for the Medicaid program will be placed on a budget for the first time. States will receive a capped amount of money per enrollee, based on the category of eligibility into which the enrollee falls. There will be five categories: elderly; blind and disabled; children; non-expansion adults; and expansion adults. The initial payment amount will be based on state Medicaid spending in 2016. It will be indexed to increases in the medical care component of the urban consumer price index, which was 3.9 percent from January 2016-January 2017. DSH payments, administrative payments, and certain beneficiaries will be exempt from the caps. If state spending exceeds the cap, states will have to pay back the excess funding the following year.

PATIENT AND STATE STABILITY FUND

The bill creates the Patient and State Stability Fund and appropriates $100 billion for the fund over nine years: 2018-2026. In 2018 and 2019, $15 billion a year is allotted, with $10 billion in each subsequent year. In 2020, the fund begins to require state contributions, gradually reaching a 50 percent match rate.

States apply for the funds and are automatically approved within 60 days unless the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services finds the state out of compliance.

The bill outlines many broad allowable uses for the funds:

- Financially assisting high-risk people to access health coverage in the individual market

- Providing incentives to appropriate entities to enter into arrangements with the state to help stabilize premiums in the individual market

- Reducing the cost of providing health insurance to high-cost users in the individual and small group markets

- Promoting insurer participation in the individual and small group markets

- Promoting access to preventive, dental, and vision services, as well as services and treatment for mental health and substance abuse disorders

- Providing payments, directly or indirectly, to health care providers for the provision of health care services specified by the administrator

- Providing assistance to reduce out-of-pocket costs for people enrolled in health insurance

A state must apply for the funds within 45 days of the bill’s enactment for 2018, or by March 31 for subsequent years. If a state does not, the CMS administrator may use its allotment to pay insurers for reinsurance purposes.

For 2018 and 2019, the formula used to calculate a state’s proportion of funding is based on two criteria. Eighty-five percent of the annual funding is based on incurred claims for benefit year 2015, and subsequently 2016, using the latest medical loss ratio data available. In order to receive a proportion of the remaining 15 percent of funding, a state must meet one of two requirements: its uninsured population for people below the federal poverty level increased from 2013 to 2015; or fewer than three insurers are offering coverage on the exchange in 2017.

Beginning in 2020, the administrator is charged with setting the allocation methodology.

OTHER NOTABLE PROVISIONS:

- Rescinds all funds for the Prevention and Public Health Fund – commonly referred to as the Obamacare slush fund – after 2019

- Increases funding for community health centers

- Prohibits for one year federal payments – including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grants, and Social Services Block Grants to states – from going to certain non-profit, family planning entities that receive more than $350 million a year in Medicaid funding and provide abortion services

- Repeals Obamacare’s actuarial value requirements for plans sold in the individual and small group markets

- Changes Obamacare’s age-rating restriction from 3-1 to 5-1, or a ratio determined by states

Next Article Previous Article